How can you summarize a year like 2023?

Perhaps the best that can be said is that, as far as the economy is concerned, it was significantly less exciting than 2022.

And that's probably not a bad thing, because in 2022, much of what was considered excitement was extremely painful: the start of a cost of living crisis that caused the biggest fall in British living standards in recorded history, and a financial collapse subsequently Liz Truss'S Mini budget.

The plan when Rishi Sunak And Jeremy Hunt They were always supposed to make the economy boring, and they partially succeeded in doing that when they came into office.

Most obviously, although government borrowing costs subsequently rose above Truss-era levels, this was largely due to higher inflation expectations rather than fears about the credibility of British government policy.

This time last year most people – current business included – assumed that 2023 would be a year of recession for the UK.

And for most of the year, that's exactly how it looked.

Both France and Germany plunged into a technical recession (The definition of this is that you suffer two consecutive quarters of economic contraction). Britain was expected to do the same.

Economic growth

But somehow it never happened.

At least not completely.

Instead, the economy was more or less stagnant for most of the year – although figures released by the Office for National Statistics just before Christmas showed this Economy shrank slightly by 0.1% in the third quarter.

Either way, this can hardly be called a positive result. Normally one would expect the UK's gross domestic product to grow by around 2-2.5% each year.

However, economic growth this year is slightly higher than most expected – although (see below) it has been helped by a colossal increase in migration.

Technically this meant the Prime Minister was meeting one of his colleagues well-respected promises He traveled to the country at the beginning of the year to stimulate the economy.

As you can see from the graph, this is nothing to brag about, especially compared to pre-pandemic developments, but it is definitely better than what many other European countries have experienced.

Cost of living

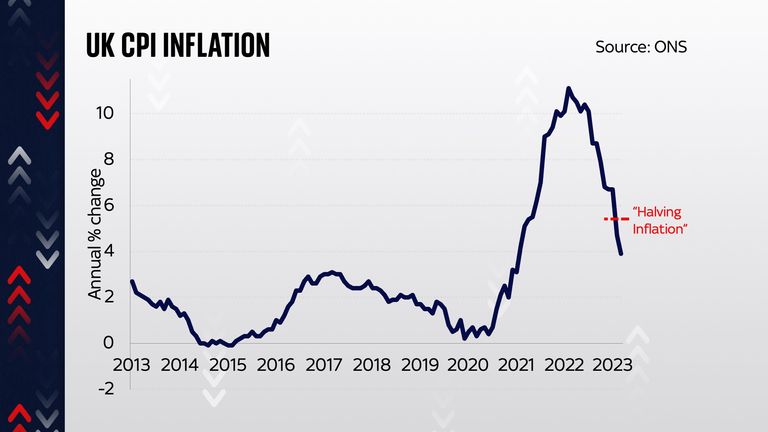

Another promise from the Prime Minister was to halve inflation this year.

At the time he made it, this promise looked pretty unremarkable considering that a) it was about controlling inflation Bank of Englandis the government's job, not the government's, and b) pretty much every economist had expected inflation to halve this year anyway.

But over the course of the year, inflation exceeded the forecasts of many of these economists, making this promise seem quite risky in the summer.

But as soon as inflation surprised positively, it also surprised negatively and fell faster than most economists had expected.

By the end of the year, the inflation rate of the consumer price index was fell to 3.9% This is close to “normal” range, although well above the Bank of England’s 2% target.

While that meant the rate actually halved (actually more than halved) over the course of the year, the cost of living crisis is far from over.

After all, inflation is simply the rate at which prices change each year. And currently prices are still 15% higher than a few years ago.

It is this increase that is currently causing severe economic difficulties.

Life doesn't get any less expensive. It's just getting more expensive a little slower than it was about a year ago.

Interest charges

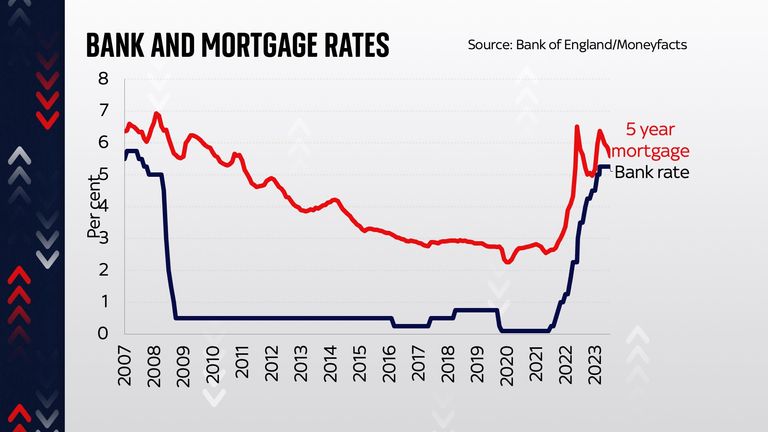

It's tempting to summarize everything Interest charges along with the other things that didn't turn out as bad as expected, but here the story is more complicated.

It's true: interest rates never rose to the 6% highs once expected at the time of the Truss mini-Budget and also during the surge in inflation during Hunt's term.

Still, they rose far more than most expected at the start of the year, up to Peak value of 5.25%. At the end of the year, the bank still insisted they would stay up for some time (and some members still voted for higher rates), but most investors expect them to be cut several times in the new year – except for 4% until the end of the year.

This affects the mortgage interest rates that most of us pay, as fixed rate mortgages are usually based on developments in the financial markets and not the bank's official interest rate. The result was that prevailing interest rates for two- and five-year fixed-rate mortgages were the same falling sharply until the end of the year.

Tax burden

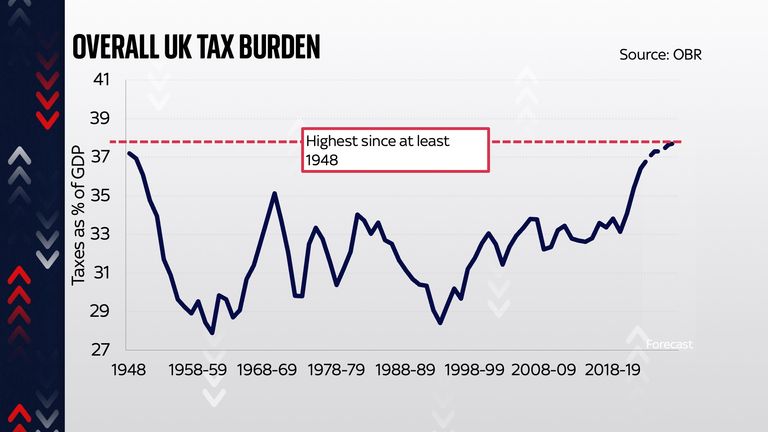

Another hot topic this year was taxation.

The government repeatedly insisted it wanted to cut them, and in the Autumn Statement the Chancellor announced a series of cuts to both workers' taxes and taxes on business investment.

The result was that the tax burden would not increase as much as it otherwise would have.

However, that is Total load is still expected to be at its highest level since the 1940s, in large part because the amounts at which people are moved into higher tax brackets have been frozen.

Higher wage inflation (due to the cost of living crisis) means more people will be taxed on their earnings at these higher levels.

This so-called “fiscal burden” means that the country is changing from a medium tax country to a high tax country.

However, this is also true for most developed countries as the costs of running expensive healthcare systems and the average age of their populations increase.

migration

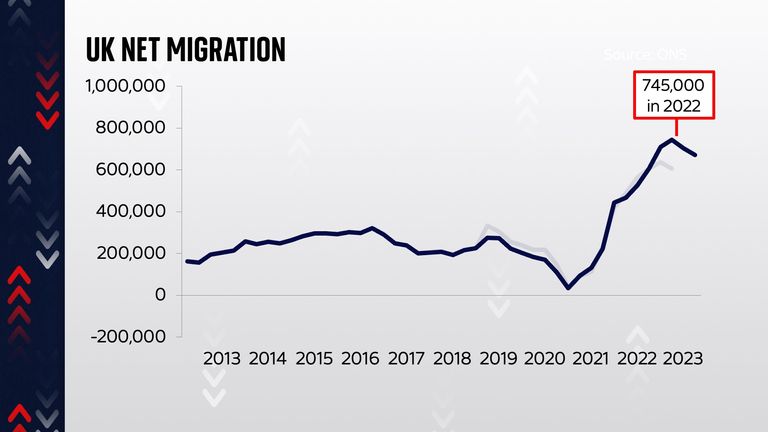

While the government spent much of its energy talking about illegal immigration and the boats coming across the Channel, the real quantitative story here was actually legal migration, which was rising to levels according to data released this year unprecedented level of 745,000 in 2022.

This climb was extraordinary in every way.

In relation to the share of the population, this is by far the largest increase in net migration since records began. And surprisingly, experts said this was primarily a consequence of new rules introduced after Brexit that made it easier for workers and students from outside Europe to come to the UK.

Migration may have been a big issue during the EU referendum, but the numbers are significantly higher today than they were then – but Britain has been swapping EU migrants with those from outside the continent – notably India and China.